Heart Murmur

Heart murmurs are unique heart sounds produced when blood flows across a heart valve or blood vessel. This occurs when turbulent blood flow creates a sound loud enough to hear with a stethoscope. The sound differs from normal heart sounds by their characteristics. For example, heart murmurs may have a distinct pitch, duration, and timing. The major way healthcare providers examine the heart on physical exam is heart auscultation; another clinical technique is palpation, which can detect by touch when such turbulence causes the vibrations called cardiac thrill. A murmur is a sign found during the cardiac exam. Murmurs are of various types and are important in the detection of cardiac and valvular pathologies (i.e., can be a sign of heart diseases or defects).

There are two types of murmur. A functional murmur is a benign heart murmur that is primarily due to physiologic conditions outside the heart. The other type of heart murmur is due to a structural defect in the heart itself. Defects may be due to narrowing of one or more valves (stenosis), backflow of blood through a leaky valve (regurgitation), or the presence of abnormal passages through which blood flows in or near the heart.

Most murmurs are normal variants that can present at various ages, relating to changes in the body with age such as chest size, blood pressure, and pliability or rigidity of structures.

Heart murmurs are frequently categorized by timing. These include systolic heart murmurs, diastolic heart murmurs, or continuous murmurs. These differ in the part of the heartbeat they make sound, during systole, or diastole. Yet, continuous murmurs create sound throughout both parts of the heartbeat. Continuous murmurs are not placed into the categories of diastolic or systolic murmurs.

Diagnostic Approach and Diagnosis

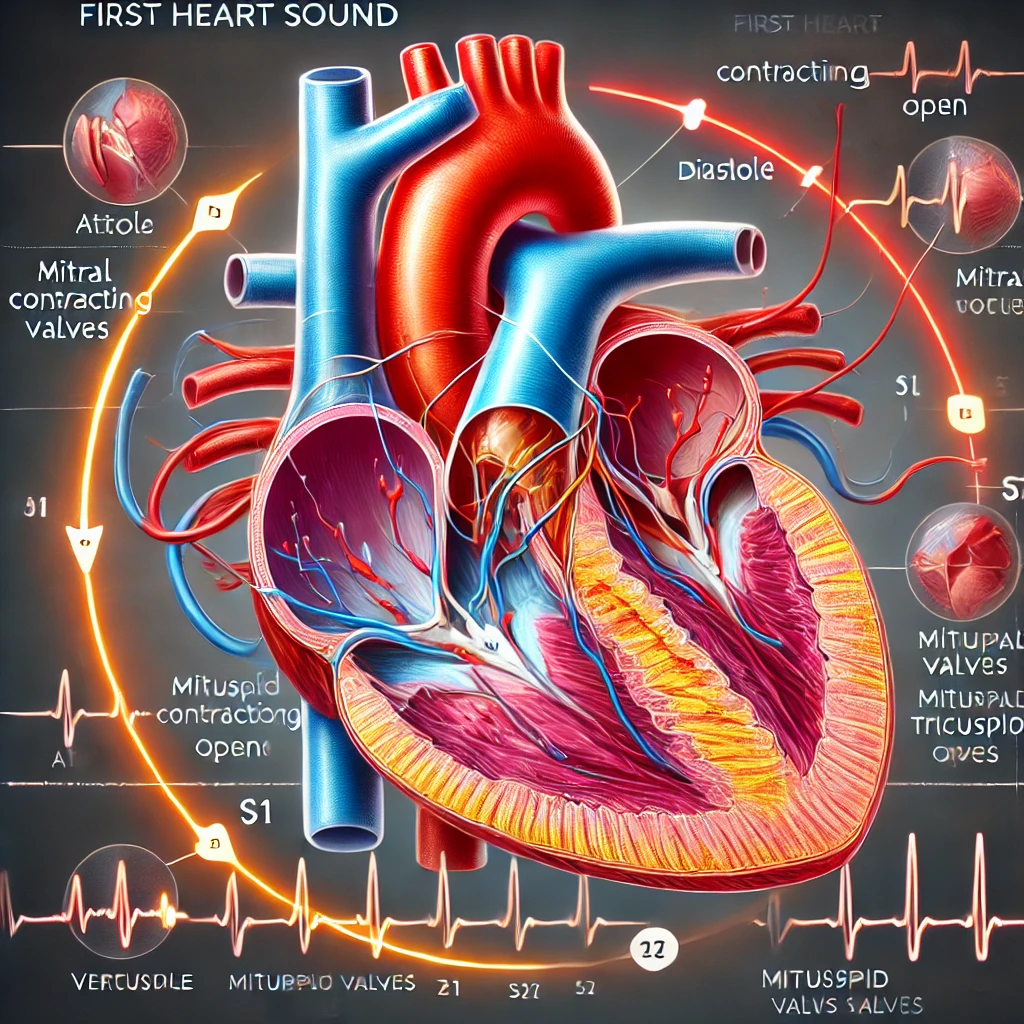

Heart Sounds

| Description | Duration | Link |

|---|---|---|

| Mitral Valve Prolapse murmur at mitral area | 12 seconds | Heart sounds of a 16-year-old girl diagnosed with mitral valve prolapse and mitral regurgitation. Auscultating her heart, a systolic murmur and click are heard. Recorded with the stethoscope over the mitral valve. |

| Mitral Valve Prolapse murmur at tricuspid area | 26 seconds | Her heart sounds while holding her breath. Recorded with the stethoscope over the tricuspid valve. |

| Mitral Valve Prolapse murmur at tricuspid area after exercising | 14 seconds | Her heart sounds during recovery after running. Recorded with the stethoscope over the tricuspid valve. |

| Physiologic systolic flow murmur | 32 seconds | Heart sounds of a healthy 17-year-old female. An innocent systolic flow murmur is audible, as well as the normal splitting of S2 on inspiration. Recorded with the stethoscope at the tricuspid. |

| Heart murmur | 55 seconds | Ventricular septal defect murmur in a 14-year-old female’s heart, heard from the mitral valve area. |

Murmurs have seven main characteristics. These include timing, shape, location, radiation, intensity, pitch, and quality.

Timing refers to whether the murmur is a systolic, diastolic, or continuous murmur.

Shape refers to the intensity over time. Murmurs can be crescendo, decrescendo, or crescendo-decrescendo. Crescendo murmurs increase in intensity over time. Decrescendo murmurs decrease in intensity over time. Crescendo-decrescendo murmurs have both shapes over time. These have a progressive increase in intensity, peak, and progressive decrease in intensity. Crescendo-decrescendo murmurs resemble a diamond or kite shape.

Location refers to where the heart murmur is usually heard best. There are four places on the anterior chest wall to listen for heart murmurs. Each location roughly corresponds to a specific part of the heart. Healthcare providers listen to these areas with a stethoscope.

| Region | Location | Heart Valve Association |

|---|---|---|

| Aortic | 2nd right intercostal space | Aortic valve |

| Pulmonic | 2nd left intercostal spaces | Pulmonic valve |

| Tricuspid | 4th left intercostal space | Tricuspid valve |

| Mitral | 5th left mid-clavicular intercostal space | Mitral valve |

Position for auscultation: The patient is most often lying on their back (supine) with the head of the bed at a slight upward angle. The head of the bed is usually at a 30-degree upward angle. Usually, the healthcare provider is standing to the right of the person they are examining. Below are positional changes that one may use:

- Left lateral decubitus (lying on the left side). This will decrease the distance from the wall of the chest to the apex of the heart. This will help to examine the point of maximal impulse. Also, this will help to hear extra heart sounds (S3 or S4).

- With the patient sitting upright.

- With the patient seated, leaning forward and holding breath after exhalation. This will decrease the distance of the chest wall to the left ventricular outflow tract. By doing so, this will help find the presence of an aortic regurgitation murmur.

Radiation refers to where the sound of the murmur travels. The rule of thumb is that the sound radiates in the direction of the blood flow.

Intensity refers to the loudness of the murmur with grades according to the Levine scale, from 1 to 6:

- 1: Only audible on listening carefully for some time

- 2: Faint but immediately audible on placing the stethoscope on the chest

- 3: Loud, readily audible but with no palpable thrill

- 4: Loud with a palpable thrill

- 5: Loud with a palpable thrill. So loud that it is audible with only the rim of the stethoscope touching the chest

- 6: Loud with a palpable thrill. Audible with the stethoscope not touching the chest but lifted just off it

Pitch may be low, medium, or high. This depends on whether auscultation is best with the bell or diaphragm of a stethoscope.

Quality refers to unusual characteristics of a murmur. For example, blowing, harsh, rumbling, or musical.

Interventions that Change Murmur Sounds

Inhalation leads to an increase in intrathoracic negative pressure. This increases the capacity of pulmonary circulation, thereby prolonging ejection time. This will affect the closure of the pulmonary valve. This finding is also called Carvallo’s maneuver. This maneuver in studies had a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 80% to 88% in detecting murmurs originating in the right heart. Positive Carvallo’s sign describes the increase in intensity of a tricuspid regurgitation murmur heard with inspiration.

- Abrupt standing

- Squatting, by increasing afterload and increasing preload. Squatting leads to an increase in systemic vascular resistance. An increase in systemic vascular resistance results in an increase in afterload. With hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy, an increase in afterload will hold the obstruction in a more open configuration. This will decrease the loudness of the murmur with HOCM.

- Handgrip maneuver, by increasing afterload. Like squatting, this will decrease the loudness of the HOCM murmur.

- Valsalva maneuver. Valsalva maneuver has utility in detecting hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM). According to one study, it has a sensitivity of 65% and specificity of 96% in HOCM. Valsalva maneuver, as well as standing, decrease venous return to the heart. As a result, this decreases left ventricular filling. With HOCM, the outflow obstruction increases with a decrease in preload. This will increase the loudness of the murmur with HOCM.

- Post ectopic potentiation

- Inhaled amyl nitrite. This is a vasodilator that diminishes systolic murmurs in left-to-right shunts in ventricular septal defects. It also reveals right-to-left shunts in the setting of pulmonic stenosis and a ventricular septal defect.

- Methoxamine

- Positioning of the patient. In the lateral decubitus position or lying on the left side. This will make murmurs in the mitral valve area more pronounced.

Anatomic Sources

Systolic

Aortic valve stenosis is a crescendo/decrescendo systolic murmur. It is best heard

at the right upper sternal border (aortic area). It sometimes radiates to the carotid arteries. In mild aortic stenosis, the crescendo-decrescendo is early peaking. Whereas in severe aortic stenosis, the crescendo is late-peaking. In severe cases, obliteration of the S2 heart sound may occur.

Stenosis of bicuspid aortic valve is like the aortic valve stenosis heart murmur. But, one may hear a systolic ejection click after S1 in calcified bicuspid aortic valves. Symptoms tend to present between 40 and 70 years of age.

Mitral regurgitation is a holosystolic murmur. One can best hear it at the apex location and it may radiate to the axilla or precordium. When associated with mitral valve prolapse, one may hear a systolic click. In this scenario, valsalva maneuver will decrease left ventricular preload. This will move the murmur onset closer to S1. Isometric handgrip will increase left ventricular afterload. This will increase murmur intensity. In acute severe mitral regurgitation, one may not hear a holosystolic murmur.

Pulmonary valve stenosis is a crescendo-decrescendo systolic murmur. One can hear it best at the left upper sternal border. It has association with a systolic ejection click that increases with inspiration. This finding results from an increased venous return to the right side of the heart. Pulmonary stenosis sometimes radiates to the left clavicle.

Tricuspid valve regurgitation is a holosystolic murmur. It presents at the left lower sternal border with radiation to the left upper sternal border. One may see prominent v and c waves in the JVP (jugular venous pressure). The murmur will increase with inspiration.

Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (or hypertrophic subaortic stenosis) will be a systolic crescendo-decrescendo murmur. One can best hear it at the left lower sternal border. Valsalva maneuver will increase the intensity of the murmur. Going from squatting to standing will also increase the intensity of the murmur.

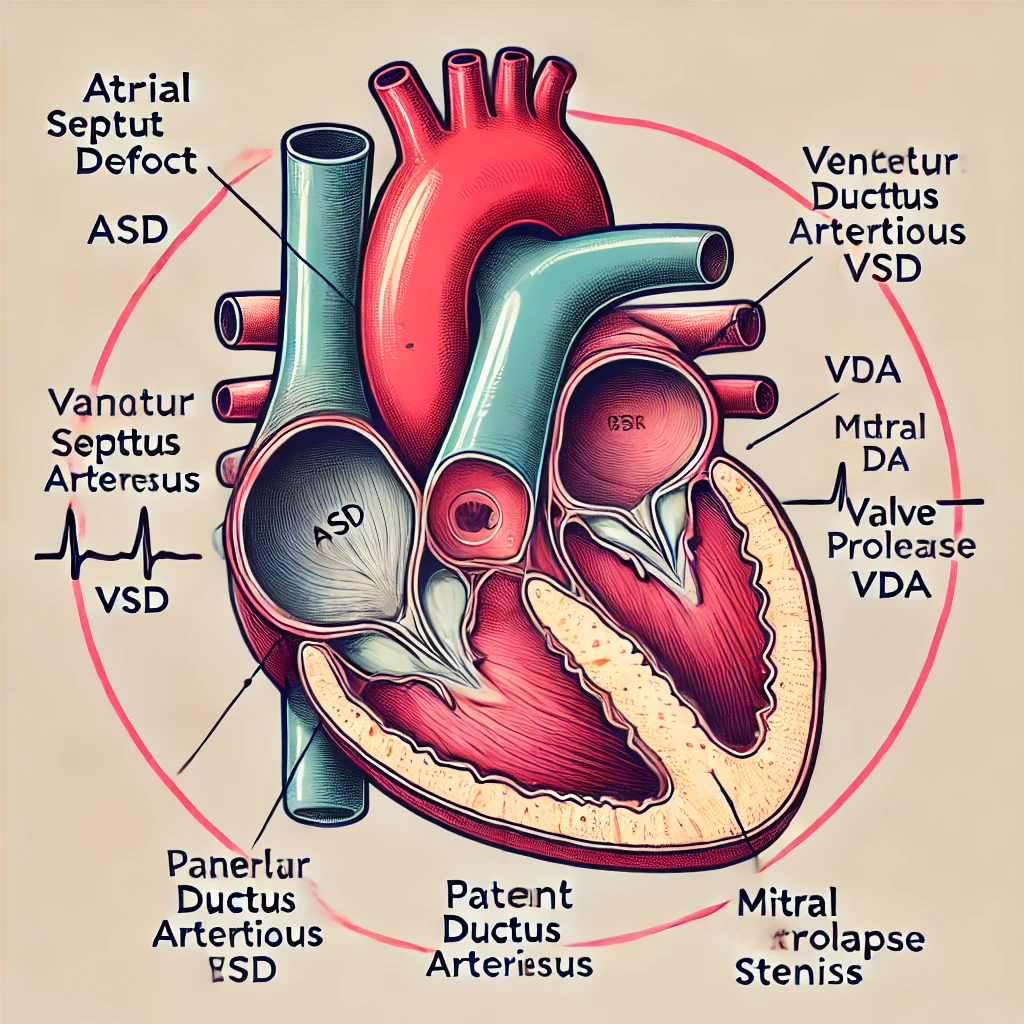

Atrial septal defect will present with a systolic crescendo-decrescendo murmur. It is best heard at the left upper sternal border. This is the result of an increased volume going through the pulmonary valve. It has association with a fixed, split S2 and a right ventricular heave.

Ventricular septal defect (VSD) will present as a holosystolic murmur. One can hear it at the left lower sternal border. It has association with a palpable thrill, and increases with isometric handgrip. A right-to-left shunt (Eisenmenger syndrome) may develop with uncorrected VSDs. This is due to worsening pulmonary hypertension. Pulmonary hypertension will increase the murmur intensity and may present with cyanosis. Read more here.

Flow murmur presents at the right upper sternal border. It may present in certain conditions, such as anemia, hyperthyroidism, fever, and pregnancy.

Diastolic

Aortic valve regurgitation will present as a diastolic decrescendo murmur. One can hear it at the left lower sternal border. One may also hear it at the right lower sternal border (when associated with a dilated aorta). Other possible exam findings are bounding carotid and peripheral pulses. These are also known as Corrigan’s pulse or Watson’s water hammer pulse. Another possible finding is a widened pulse pressure.

Mitral stenosis presents as a diastolic low-pitched decrescendo murmur. It is best heard at the cardiac apex in the left lateral decubitus position. Mitral stenosis may have an opening snap. Increasing severity will shorten the time between S2 (A2) and the opening snap. For example, in severe MS the opening snap will occur earlier after A2.

Tricuspid valve stenosis presents as a diastolic decrescendo murmur. One can hear it at the left lower sternal border. One may see signs of right heart failure on exam.

Pulmonary valve regurgitation presents as a diastolic decrescendo murmur. One may hear it at the left lower sternal border. A palpable S2 in the second left intercostal space correlates with pulmonary hypertension due to mitral stenosis.

The cooing dove murmur is a cardiac murmur with a musical quality (high pitched). Associated with aortic valve regurgitation (or mitral regurgitation before rupture of chordae). It is a diastolic murmur heard over the mid-precordium.

Continuous and Combined Systolic/Diastolic

Patent ductus arteriosus may present as a continuous murmur radiating to the back.

Severe coarctation of the aorta can present with a continuous murmur. One may hear the systolic component at the left infraclavicular region and the back. This is due to the stenosis. One may hear the diastolic component over the chest wall. This is due to blood flow through collateral vessels.

Acute severe aortic regurgitation may present with a three-phase murmur. First, a midsystolic murmur followed by S2. Following this is a parasternal early diastolic and mid-diastolic murmur (Austin Flint murmur). The exact cause of an Austin Flint murmur is unknown. Hypothesis is that the mechanism of murmur is from the severe aortic regurgitation. In severe aortic regurgitation, the jet vibrates the anterior mitral valve leaflet. This causes a collision with the mitral inflow during diastole. As such, the mitral valve orifice narrows. This results in increased mitral inflow velocity. This leads to the jet impinging on the myocardial wall.

Ruptured aortic sinus (sinus of Valsalva) may present as a continuous murmur. This is an uncommon cause of continuous murmur. One may hear it at the aortic area and along the left sternal border.

Types and Disease Associations

Continuous machinery murmur, at the left upper sternal border

- Classic for a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA). Signs of infants associated with serious cases of PDA are poor feeding, failure to thrive, and respiratory distress. Other examination findings may include widened pulse pressures and bounding pulses. A machinery murmur is also known as a Gibson murmur.

Systolic murmur loudest below the left scapula

- Classic for a coarctation of the aorta. Coarctation of the aorta is narrowing of the aorta. This can occur in Turner’s Syndrome, (gonadal dysgenesis). Turner’s Syndrome is an X-linked disorder with absence of one X-chromosome. Other exam findings of coarctation of the aorta include radio-femoral delay. This is when the femoral pulse is later than the radial pulse. The pulses in the lower extremity may be weaker than those of the upper extremity. Another exam finding is of varying blood pressure in the upper and lower extremities. This presents as higher blood pressure in the arms and lower blood pressure in the legs.

Harsh holosystolic (pansystolic) murmur at the left lower sternal border

- Classic for a ventricular septal defect (VSD). This may lead to the development of the delayed-onset cyanotic heart disease known as Eisenmenger syndrome. Eisenmenger syndrome is a reversal of the left-to-right heart shunt. This is the result of hypertrophy of the right ventricle over time. This causes a right-to-left heart shunt. The VSD allows deoxygenated blood to flow from the right to left side of the heart. This blood bypasses the lungs. The lack of oxygenation in the pulmonary circulation results in cyanosis.

Widely split fixed S2 and systolic ejection murmur at the left upper sternal border

- Classic for a patent foramen ovale (PFO) or atrial septal defect (ASD). A PFO is lack of closure of the foramen ovale. At first, this produces a left-to-right heart shunt. This does not produce cyanosis, but causes pulmonary hypertension. Longstanding uncorrected atrial septal defects can also result in Eisenmenger syndrome. Eisenmenger syndrome can result in cyanosis.

Management

A medical provider (e.g. doctor) may order tests for further evaluation of a heart murmur. The echocardiogram is a common test used. This is also known as an “echo” or ultrasound of the heart. It shows the heart structures and blood flow through the heart. Further testing is usually done when symptoms that may be of concern are present.

The need for treatment depends on the diagnosis and severity. In some cases, the condition causing the heart murmur may prompt monitoring. Sometimes, heart murmurs disappear on their own. This happens when the cause of the heart murmur is no longer present. Monitoring will help determine how the condition changes. It may stay the same, worsen, or improve. In other cases, the condition causing the heart murmur may not prompt any further tests.

Treatment ranges from medication to surgeries.

References

- “Patient education: Heart murmurs (The Basics)”. UpToDate. 25 March 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- Braunwald’s heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine. Douglas P. Zipes, Peter Libby, Robert O. Bonow, Douglas L. Mann, Gordon F. Tomaselli, Eugene Braunwald (Eleventh ed.). Philadelphia. 2019. ISBN 978-0-323-46342-3. OCLC 1030994993.

- Bickley, Lynn S. (2021). Bates’ guide to physical examination and history taking. Peter G. Szilagyi, Richard M. Hoffman, Rainier P. Soriano (Thirteenth ed.). Philadelphia. ISBN 978-1-4963-9817-8. OCLC 1153338113.

- “Cardiac thrill”. nih.gov. Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- “heart murmur”. Dorland’s Medical Dictionary.

- “continuous murmur”. Dorland’s Medical Dictionary.

- “Heart murmur: characteristics”. LifeHugger. Archived from the original on 24 November 2010. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

- Orient JM (2010). “Chapter 17: The Heart”. Sapira’s Art & Science of Bedside Diagnosis (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwers Health. p. 339. ISBN 978-1-60547-411-3.

- Freeman AR, Levine SA (1933). “Clinical significance of systolic murmurs: Study of 1000 consecutive ‘noncardiac’ cases”. Ann Intern Med. 6 (11): 1371–1379. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-6-11-1371.

- “Medline Plus Medical Dictionary, definition of ‘cardiac thrill'”. Archived from the original on 27 May 2011.

- Lembo N, Dell’Italia L, Crawford M, O’Rourke R (1988). “Bedside diagnosis of systolic murmurs”. N Engl J Med. 318 (24): 1572–8. doi:10.1056/NEJM198806163182404. PMID 2897627.

- Maisel A, Atwood J, Goldberger A (1984). “Hepatojugular reflux: useful in the bedside diagnosis of tricuspid regurgitation”. Ann Intern Med. 101 (6): 781–2. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-101-6-781. PMID 6497192.

- Harrison’s Internal Medicine 17th, chapter 5, “Disorders of the cardiovascular system,” question 32, self-assessment and board review.

- Harrison’s Internal Medicine 17th, chapter 5, “Disorders of the cardiovascular system,” questions 86-87, self-assessment and board review.

- Cumming, Gordon R. (1963). “Amyl Nitrite Induced Changes in Cardiac Shunts”. Br. Heart J. 25 (4): 521–531. doi:10.1136/hrt.25.4.525. PMC 1018027. PMID 14047161.

- Kohno, Kenji; Hiroki, Tadayuki; Arakawa, Kikuo (1981). “Aortic regurgitation with dove-coo murmur with special references to the mechanism of its generation using dual echocardiography”. Japanese Heart Journal. 22 (5): 861–869. doi:10.1536/ihj.22.861. PMID 7321208. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- John Oshinski; Robert Franch, MD; Murray Baron, MD; Roderic Pettigrew, MD (1998). “Images in Cardiovascular Medicine Austin Flint Murmur”. Circulation. 98 (24): 2782–2783. doi:10.1161/01.cir.98.24.2782. PMID 9851968.

- “Blaufuss Multimedia – Heart Sounds and Cardiac Arrhythmias”. Medical Multimedia Laboratories. Archived from the original on 29 August 2007. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- Topi, Bernard; John (September 2012). “An uncommon cause of a continuous murmur”. Experimental and Clinical Cardiology. 17 (3): 148–149. PMC 3628432. PMID 23620707.

- “Gibson murmur”. The free dictionary.com. Retrieved January 27, 2016.

Also read

- A Comprehensive Look at the Diagnosis of Tetralogy of Fallot

- Clinically Significant Pulse Patterns: A Comprehensive Guide to Diagnosis

- Recognizing the Signs and Symptoms of Tetralogy of Fallot

- Characteristics of Cardiac and Non-Cardiac Chest Pain and How to Diagnose a Case by Pain’s Nature

- Shattering Schizophrenia: Unraveling the Mysteries of a Complex Disorder